Future of Work - The Conundrum with Artificial Intelligence and Ethics

The world realised the need for international standards to govern AI as digital technologies develop rapidly

Importance of Ethics in a Virtual World

Digital tools - increasingly sophisticated AI applications, interoperable edge computing and Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and autonomous technologies - underpin the functioning of cities and critical infrastructure today and will play a key role in developing resilient solutions for tomorrow’s crises. Yet these developments also give rise to new challenges for states trying to manage the existing physical world and this rapidly expanding digital domain. Large and complex issues like commercialised piracy, data-enabled anocracies, misinformation and disinformation, and adverse use of frontier technologies are becoming mainstream[1]. In this context, conversations around the ethical use and deployment of frontier technologies –particularly artificial intelligence – have become mainstream, crossing from the domain of corporations into parliaments and multilateral institutions.

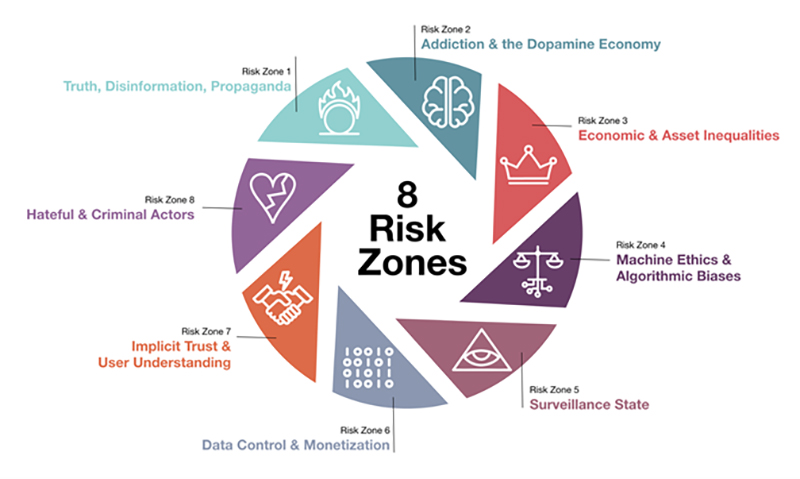

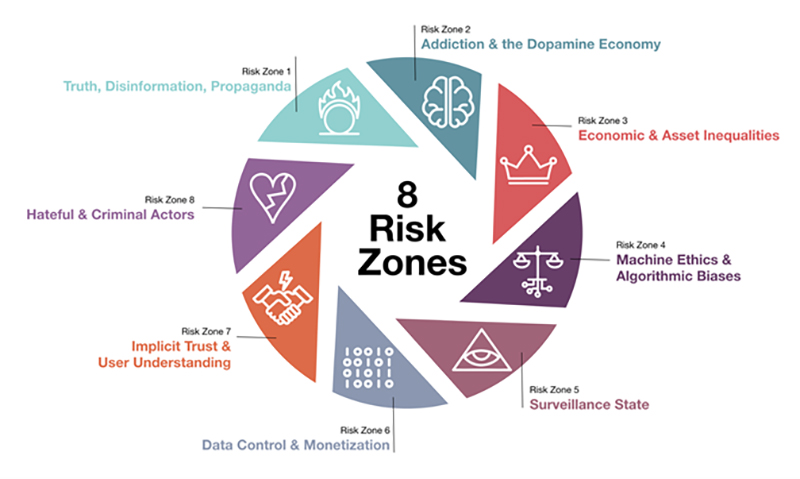

In 2022, the World Economic Forum[2] laid down eight key risk zones emanating from the use and deployment of frontier technologies (as in the graphic below).

Private sector-led development of powerful dual-use (civilian and military) technology makes regulatory guardrails even more essential. However, commercial incentives and national security-driven “tech wars” may outstrip regulatory efforts to curb adverse societal and security outcomes.

The production of AI technologies is highly concentrated in a singular, globally integrated supply chain that favours a few companies and countries. This creates significant supply-chain risks that may unfold over the coming decade. For example, export controls over the early stages of the supply chain (including minerals) could raise overall costs and lead to persistent inflationary pressures. Restricted access to more complex inputs (such as semiconductors)could radically alter a country's trajectory of advanced technological deployment. The extensive deployment of a small set of AI foundation models, including in finance and the public sector, or overreliance on a single cloud provider could give rise to systemic cybervulnerabilities, paralysing critical infrastructure[3].

This paper intends to concentrate on risk zone 5, namely the “surveillance state,” emphasising“ surveillance capitalism” and how guardrails envisioned now are necessary yet grossly insufficient endeavours.

Surveillance Capitalism

Appreciating some time-tested and accepted norms as we dive into this mainstream reality is essential. The holistic development of an individual is a multifaceted process that encompasses the physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual aspects of human life. Integrating ethical and human values is a crucial factor in this development process. Ethics are pivotal in shaping how people interact with each other and the world around them. In short, morals are the behaviour that society judges.

Ethics are the behaviours that your conscience judges. Depending on where and when we are born, we draw a line and say, from there to here is good; from there to here is terrible. And things start to get difficult closer to the line. The interplay between morals and ethics is pertinent to appreciate, starting with understanding the distinctions between the two.

Morals are the behaviours that society judges by. Ethics are the behaviours that your conscience judges.

Surveillance capitalism is broadly defined as “a new economic order” that claims human experience as (a) free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction and sales, (b) a parasitic economic logic in which the production of goods and services is subordinated or the new global architecture of behavioural modification[4].

In economics, surveillance capitalism is the “subordination” of means of production to a complex and comprehensive means of “behavioural modification”.

The two definitions represent the underpinnings of almost all activities we see today across the worldwide socio-political, economic and commercial systems. We are all aware that our digital experiences capture significant amounts of behavioural data from us that are then utilised to customise those experiences – thereby giving advertisers more critical insights into target customers and monetisation that translates to immense revenues for platform providers (Google, Facebook, Baidu, etc.) We may not be aware of the amount of “surplus” behavioural data – voices, personalities, emotions, reactions, and responses in social feeds available every second.

Capturing such behavioural data has been significantly enhanced by intervening through nudges, suggestions, offers, et al. in a manner that permits the herding behaviour of users toward profitable outcomes – and that is the digital world we live in today. Shoshana writes,

With this reorientation from knowledge to power, it is no longer enough to automate information flows about us; the goal is to automate us.

Large and complex issues like commercialised piracy, data-enabled anocracies, misinformation and disinformation, and adverse use of frontier technologies are becoming mainstream.

Our advances with machine learning and now artificial intelligence have contributed to significant growth and borderless expansion of this capture and utilisation of behavioural surplus, to the extent that traditional economics – production, consumption, distribution and exchange – is being replaced by a far more insidious form of capitalism where behavioural modification is being marketed as the democratisation of knowledge. At the same time, the model remains anti-inclusive, perfunctorily democratic, perhaps anti-social, and significantly ambiguous regarding morality and ethics.

A Nebulous Future with Ethics

In 2017, the first deliberation on AI[5] and its ethical implications was held in lines similar to the 1975 Conference on Recombinant DNA[6]. The 23 principles laid the foundation for the moral institution of AI in various endeavours worldwide. Unfortunately, the quest for building new digital revenues in a hyper-connected world pushed commitments toward the ethical implementation of AI technologies onto the back burner.

Multilateral institutions like ASEAN and the EU are developing governance principles for the ethical use of AI and are looking to institute their versions of AI governance rules and acts.

Fast forward, today owing to the advent of generative AI and consequences with general AI deployment, seen particularly in the manifestation of emergent risks around deep fakes, misinformation/ disinformation, geopolitical interferences and narratives permeated through AI- have all led to a reassessment of ethics with AI deployment, thereby debunking the long-held belief that self-governance is the best way to enable and enhance economic endeavours. It is fast being replaced by governments and multilateral stakeholders demanding accountability from large corporations that own data and leverage technologies for purely capitalist pursuits.

As we deepen our comprehension of AI’s effects, advantages, and possible impacts, we must also work on regulating its use globally.

In this context, the world realised the need for international standards to govern AI, building on the Asilomar agreement. Led by UNESCO, 193 member nations embarked on formulating the first global normative instrument[7] on the ethics of artificial intelligence in 2021, and the OECD states that AI systems should be robust, secure and safe throughout their entire lifecycle to function appropriately and avoid posing unreasonable safety risks. However, they have been more advocative than action/compliance-oriented, given the complexity of combining a variegated set of standards across industries and countries (particularly in nations where privacy protection laws are either onerous or poor).

Multilateral institutions like ASEAN and the EU are already building governance principles around the ethical use of AI alongside nations that are looking to institute their versions of AI Governance rules and acts. How and what will these efforts translate to, and will they turn globalisation on or off today?

In Conclusion

Would we be at the point where the world pushes a “compliance economy” narrative, or would “self-governance” no longer be relevant? We observe the dichotomy between private-sector surveillance capitalism and the government’s responsibility to ensure a level playing field. However, we may be missing the point that, eventually, the consumer world seems not to care about ethics and its interpretations as much as institutions and some conscientious leaders seem to. After all, we willingly and actively contribute to the world of surveillance capitalism and abhor any governance-centric interpretations of the proliferation of such technologies and the solutions being built on them. The vociferous pretest to ban TikTok in the USA is a case in point.

I believe a time will soon come when we will be left with little choice but to establish guardrails right now or deal with an ambiguous, uncontrolled, and non-human future in which the species’ superiority will no longer hold.

References:

[1] Please refer to our knowledge paper, “Future of Work—Reimagining a New World Order,”2023.

[2] Source: Global Risks Report 2022; www.weforum.org

[3] Excerpt from the Global Risks Report 2024, by the World Economic Forum (page 51); www.weforum.org

[4] Source: “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism – The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power”, Shoshana Zuboff; Hachette Book Group, 2020.

[5] The Future of Life Institute organised the Asilomar Conference on Beneficial AI, held January 5–8, 2017, at the Asilomar Conference Grounds in California. More than 100 thought leaders and researchers in economics, law, ethics, and philosophy met at the conference to address and formulate principles of beneficial AI. Its outcome was creating a set of guidelines for AI research – the 23 Asilomar AI Principles. Information on their activities, programmes, etc., can be found at www.partnershiponai.org.

[6] The Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA was an influential conference organised by Paul Berg, Maxine Singer, and colleagues to discuss the potential biohazards and biotechnology regulation, held in February 1975 at a conference centre at Asilomar State Beach, California. A group of about 140 professionals (primarily biologists, but also including lawyers and physicians) participated in the conference to draw up voluntary guidelines to ensure the safety of recombinant DNA technology (simply put, mixing DNA from different species to build new ones). The conference also placed scientific research more into thepublic domain and can be seen as applying a version of the precautionary principle (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Precautionary_principle).

[7] Complete details of this instrument are available via the link: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137. It is a result of three standard bodies – International Telecoms Union (www.itu.int), International Electrotechnical Commission (www.iec.ch), and International Organization for Standards (www.iso.org) – that come together to form the World Standards Cooperation (www.worldstandardscooperation.org)

Bobby Varanasi is the Founder of Regenerative Futures (formerly Matryzel Consulting), an independent advisory firm focused on global sourcing, M&A, carbon management &circular economy practices. It is acknowledged as one of the World’s “Best of the Best Outsourcing Advisory Firms” and one of the top 20 best outsourcing advisory firms for four years (2013-2015, 2019). He brings over two decades of experience in consulting and management across Technology, Business Services and building global businesses. He advises federal governments across North & South America, Middle East/ North Africa, Asia-Pacific and Australia, Fortune 500 customer organisations, and emerging market entrepreneurs on strategy, growth, sourcing, expansions, mergers and acquisitions, and inter-party trust ecosystems.