Future of Work: Implications with Man-Machine Interplay

AI differs from all other technological inventions we have built over the past century, and the answer lies in understanding the word “intelligence” in itself.

Human Labour and Its Replacement

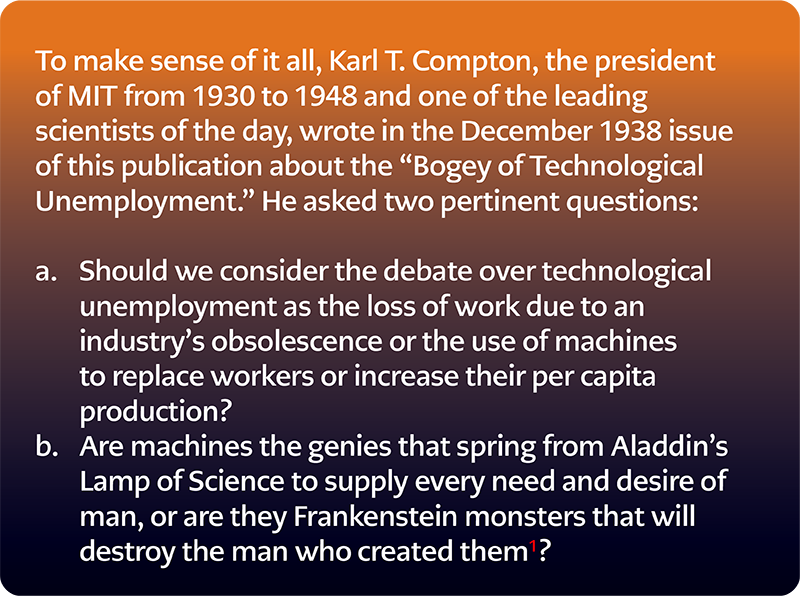

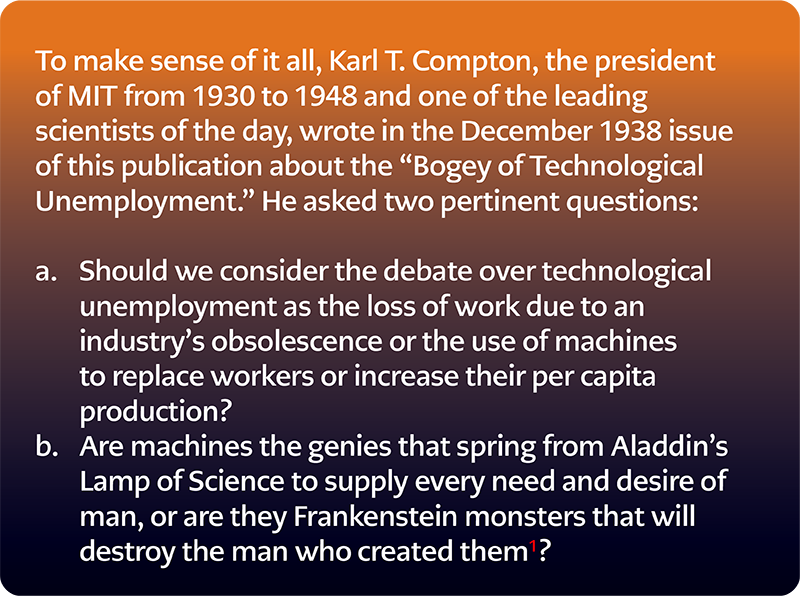

In 1930, the prominent British economist John Maynard Keynes warned that we were “being afflicted with a new disease” called technological unemployment. Labour-saving advances, he wrote, were “outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour.” There were examples everywhere. New machinery was transforming factories and farms. Were the impressive technological achievements that made life easier for many also destroying jobs and wreaking havoc on the economy?

Such questions have plagued the industrial world in various ways, with the common underlying theme that advanced technologies and machines were and continue to replace human labour. Some leading Silicon Valley techno-optimists even postulate that we’re headed toward a jobless future where artificial intelligence (AI) can do everything. In such scenarios, it is crucial to appreciate Shoshana Zuboff’s poignancy about “behavioural surplus” as another substantial manifestation of replacing human labour as a new means of enhancing productivity2.

It is a foregone conclusion that all doomsday predictions of mass unemployment have almost always been unfounded. Growth continued to be derived through the optimal deployment of humans and machines, resulting in the discrete disappearance of specific jobs but not catastrophic unemployment altogether, where industries disappeared. Is it, therefore, pertinent to continue deliberating about job replacements and losses anymore, even with the advent of AI – which is being termed the most significant evolution of mankind after industrialisation – or is there a need to discern the underlying complexities and nuances that seem to be getting lost in translation within the narrow context of capital and labour?3

We must understand AI’s “socio-cultural” and “humanistic” implications on the workforce and society.

AI as a Capital Asset

Human intelligence has and continues to be complemented by the increasing complexity and sophistry of machines – industrial and consumer – in more pervasive ways than was ever envisaged at the turn of the last century. However, with all the grandeur associated, the world has seen a net increase in productivity and yield from each ounce of human labour. While many believe that such gains can be had forever, there does come a point when the value derived becomes marginal and commoditised.

Continued increases to efficiencies have, at some point, plateaued out, necessitating either an upheaval or a fundamental shift in input sophistication to obtain greater productivity at lower price points. Faster, cheaper, and more accessible are the three mantras we continue to profess as justifications for all innovations/ improvements. Over time, however, most such endeavours lose their sheen and become utilities in themselves. In such scenarios, there is no longer “innovation”.

Instead, they are just myriad new ways of accomplish- ing the same goals. This is a crucial factor to appreciate when assessing the “value” of a new technology/ machine in the context of human endeavour.

The general argument is that AI differs from all other technological inventions we have built over the past century. The answer lies in understanding the word “intelligence” in itself; for the unversed, let’s delve into what is collectively known as “human intelligence”4. It is the sum of mental capacities such as abstract thinking, understanding, communication, reasoning, learning and memory formation, action planning, and problem-solving.

It involves gathering, storing, retrieving and analysing information, making decisions and taking action. Interestingly, underlying experiences driven by exposure to culture, education, location, social circumstances, past incidents, hopes and feelings contribute to such decisions and actions (collectively known as Human Biases)5.

Meanwhile, “artificial intelligence” is the science of making machines that can think like humans. Manifestly, however, AI refers to computer systems capable of performing complex tasks that historically only humans could do, such as reasoning, making decisions, or solving problems.

It is pertinent to appreciate a fundamental difference we witness today as we evaluate assets—particularly labour and machines/ technologies. For a long time, machines have complemented labour competencies relating to tasks, with speed, efficiency, and accuracy guiding decisions about leveraging a machine instead of a human.

This industrial logic has long been pervasive, leading to machines being treated as “capital assets” while labour was considered an expense. Interestingly, we have finally come around to revisiting this logic. It has now been fundamentally altered with discussions around the constituent element comprising both humans and machines—intelligence.

Now that machines are perceived as “intelligent if not better”6 than human intelligence, the entire conversation around treating machines as just capital assets is no longer sufficient. In this context, labour has moved down the pecking order of importance, with current trends indicating a sanguinity toward calling it an asset because it never was treated thus. Consequently, however, for the first time in human history, labour as an input factor to production is being perceived as no longer necessary, and some even go to the extent that labour only complicates productive endeavours and, therefore, its complete replacement/elimination may be better for humanity7.

Simply put, AI is beginning to do what human intelligence cannot do (any longer).

Workplaces and AI

The concept of meaningful work has recently received increased attention in philosophy and other disciplines. Doing meaningful work leads to higher job satisfaction and increased worker well-being, and some argue for a right to access it. Recent research on the impact of robotisation on meaningful work was undertaken by identifying five critical aspects of meaningful work - pursuing a purpose, social relationships, exercising skills and self-development, self-esteem and recognition, and autonomy – and concluded that there are significant positive and negative impacts to robotisation, alongside ambiguity with ethical issues8.

The summary arguments that meaningful work must be distinguished from robotic/ transactional work are generally clustered around job satisfaction, worker well-being, a sense of justice, and the value of goods tied to social contribution and community. Since the burdens and benefits connected to work are regulated by our public institutions, a just society should protect people’s access to meaningful work.

On the other hand, a relentless and unyielding pursuit of garnering, deciphering, and understanding myriad complexities with information has resulted in the transformation of automated technologies from be- ing enablers of transactional rigour (read efficiencies, speed, accuracy) to harbingers of new information, manifestly on display in many economic sectors like healthcare, astrophysics, geology, pharmaceuticals, medicine, et al. Simply put, AI is beginning to do what human intelligence cannot do (any longer).

How would the workplace of the future look? In just the past few years, we have gone from treating bots as input resources (and thereby needing to be treated as such on balance sheets—resulting in deliberations around taxing such deployments) to equality of rights alongside humans (and consequently included into the ambit of HR policies in enterprises, as unsuccessfully tried by HR consulting firm Lattice)9.

Significant questions exist about integrating AI into the workforce and how one can successfully manage coexistence (if any) between humans and intelligent machines. The argument that algorithms would replace humans where transactional rigour is needed seems simplistic. Instead, positing that workplace AI applications would have an indirect influence through the development of new, modified, or unmodified worker routines (rather than directly influencing worker productivity itself) seems logical and acceptable.

Further, while AI integration into organisational strategy brings ‘’deep’’ changes to jobs and the workforce, we are yet to understand the magnitude of such changes. AI-powered technologies associated with losing human skills, such as driverless vehicles and flying drones, have yet to work independently of human supervision. Even if such projected perfection of workplace AI is finally achieved, it is still being determined whether a complete replacement of human workers with workplace AI is politically, socially, and economically feasible.

AI is the science of making machines that can think like humans.

On the other hand, human workers are doubtful about AI decisions, recommendations, and responses and might perceive AI augmenting their abilities as being observed by intelligent systems and spied on. Also, the empirical literature10 around workers’ trust in workplace AI relies on short-term, small sample, and experimental studies. Further, in the long run, when the extent of AI replacing workers in the workplace is known, the development of workers’ trust in workplace AI is likely to change11.

In Conclusion

The debate around job replacements, diminishing value of human labour (with inabilities to handle complexities), and consequential woes with policy and corporate behaviour that limit maximisation of value through intelligent machines need to be tempered with detailed and specific thought processes and research, actions and policy constructs that include all stakeholders – corporations, civil societies, governments, and transnational contributors – in a meaningful manner where morals and ethical obligations must play as important a role as the benefits gained from economic and scientific endeavours.

Much of the current discussions around AI and its ability to completely circumvent human labour is mostly noise, taking our attention away from matters of more significance and complexity. We can no longer hide behind classical economic theories around the production-consumption spectrum with myopic changes to policies, corporate behaviour, or governmental policy constructs.

The interplay between man and machine has reached a point of no return – with the stakes too high to remain transactional with our endeavours – corporate or governmental. We must understand AI’s “socio-cultural” and “humanistic” implications on the workforce and society. It is not an “economic” argument - anyone doing so is barking up the wrong tree.

Sources:

- https://www.technologyreview.com/2024

- “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism – The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power”, Shoshana Zuboff; Hachette Book Group, 2020.

- I use “labour” throughout this paper to indicate “human endeavour” alone.

- For greater insights on what Human Intelligence is, please review https://www.clickworker.com

- Specifics around the multiple types of cognitive biases that distort or influence the human mind are found at https://www.verywellmind.com

- For specifics around the eight types of intelligence that comprise human cognisance, please refer to https://www.clickworker.com/

- This gives rise to other significant concerns, particularly around incomes, sustenance, survival of the species, etc., and consequential discussions around Universal Basic Income, the collapse of the capitalistic world, the rise of decentralised structures, and many more topics that are considered out of scope for this paper. For details, please reach out to the author.

- Greater details about this research and analysis are found at https://shorturl.at/Cvhc3

- On July 9, 2024, the HR consulting firm LATTICE tried to treat AI bots like humans by giving these digital workers “official employee records” in the organisation. Such digital workers would be securely onboarded, trained, assigned goals, performance metrics, appropriate systems accesses, and even a manager, just as any person would be. This policy was withdrawn after significant backlash from employees a few days later.

- Empirical literature by Gilksons and Wooley; https://journals.aom.org/doi

- Detailed analyses and research are found at Worker and workplace Artificial Intelligence (AI) coexistence: Emerging themes and research agenda - ScienceDirect

Bobby Varanasi is the Founder of Regenerative Futures (formerly Matryzel Consulting), an independent advisory firm focused on global sourcing, M&A, carbon management & circular economy practices. It is acknowledged as one of the World’s “Best of the Best Outsourcing Advisory Firms” and one of the top 20 best outsourcing advisory firms for four years (2013-2015, 2019). He advises federal governments across North & South America, Middle East/ North Africa, Asia-Pacific and Australia, Fortune 500 customer organisations and emerging market entrepreneurs on strategy, growth, sourcing, expansions, mergers and acquisitions, and inter-party trust ecosystems.