Innovations in Practice: Nature in Oil Palm

Wild Asia collaborates with various partners to develop nature-based solutions that support smallholders’ and growers’ sustainable oil palm journeys.

Robber flies found on Monkey’s potato (Coleus monostachyus), one of the beneficial plants for habitat islands.

A bagworm outbreak is the biggest nightmare for oil palm farmers. One of the most destructive pests, these leaf-eating insects (common species: Metisa plana and Pteroma pendula), can reduce oil palm yields by up to 40%. A conventional practice to control bagworm outbreaks is to inject the tree trunks with chemical insecticides.

“When I think about the costs (of chemicals) and the potential damage to the trees and environment in the long-term, the ‘weaver-ant tactic’ seems a better option,” says independent smallholder Long Tijah Dongkin. Using weaver ants to combat bagworms is common amongst Long Tijah’s Semai Orang Asli (indigenous) community in Perak. They would forage for weaver ant nests in the forest and haul them to their farms.

Less than 10 km from Long Tijah’s farm, farmer Chow Chan Hoi from Kampung Sungai Kroh intercrops his oil palm with 10 soursop (Annona muricata) fruit trees to attract weaver ants to combat bagworms. He learned this technique by word of mouth.

“I don’t know how effective it is. But I’ve been spared from bagworm attacks so far. Also, we can savour the soursops during the fruiting season,” says Chow, smiling. He does manual weed control and hasn’t applied pesticides on his farm for four years.

“It’s good to let the soil ‘breathe’ and regenerate,” he asserts.

A five-minute drive from Chow’s farm, Mat Jailani Arshad’s farm resembles a verdant oasis thrumming with insects. Pockets of woody shrubs like coral-pink pagoda flowers and purplish-red straits rhododendrons nestle amidst the palm trees as butterflies, bees, and wasps hover about. These native flowers draw beneficial insects such as wasps and other predators of bagworms. He also grows coral vines (Antigonon leptopus), a non-native beneficial plant, to attract stingless bees (Heterotrigona itama) for his honey enterprise. His farm has been chemical-free for eight years. His palm trees and soil are nourished with homemade compost and enzyme liquid fertilisers instead of synthetic fertilisers.

“My farming costs are low, and my yields are high,” declares Mat Jailani. “More importantly, I enjoy pottering around my lush farm every morning.”

Mat Jailani’s habitat island, a 3m-by-9m plot planted with selected flowering/beneficial plants.

Nature-Positive Farming Approach

What these farmers have in common is their espousal of nature-friendly fixes in their farm management. They learn from decades of experience that ‘conventional’ farming practices with excessive chemicals lead to degraded soil, affecting crop yields and biodiversity loss. Pest control solutions like using weaver ants to control bagworms are not merely old wives’ tales. Studies have revealed that Asian weaver ants (Oecophylla smaragdina) are a successful biological control agent (BCA) against damaging pest infestations in oil palm plantations.

These MSPO (Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil) - certified smallholders are members of Wild Asia’s WAGS BIO scheme, a production system designed to help oil palm farmers switch from ‘conventional’ agriculture to regenerative agriculture. As WAGS BIO farmers, they receive training and support to adopt regenerative farming practices.

Over the years, Wild Asia has collaborated with partners like the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH), Rainforest Alliance, and CarbonSpace, which help support and validate these nature-positive approaches.

Two recent projects involved collaborations with Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN), a coalition of non-profit organisations in America, Africa, Europe, and Asia, and the University of Cambridge to design nature-based solutions for managing oil palm.

The SAN-Ferrero Project

In 2020, Wild Asia teamed up with SAN on a project to promote practical, nature-based solutions for integrated pest management (IPM), biodiversity-friendly farming practices and profitability of oil palm producers.

Funded by Ferrero, one of the largest confectionery producers in the world, the project involves an international team of entomologists, ecotoxicologists, botanists and ecologists from Wild Asia, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), UK-based CABI, US-based Oregon State University and Costa Rica-based Scrum Agroecologia.

The project aims to introduce habitat islands for “beneficial” insects that prey on pests (defoliating insects like bagworms) that harm palm trees.

Each ‘habitat island’ is a 3m-by-9m plot planted with selected flowering/ beneficial plants. These plants serve as a food source or provide refuge for a wide variety of beneficial insects, such as parasitoids and scavengers, which are predators of bagworms or other pests. These habitat islands or plant beds are placed between palm trees, borders of canals, or internal roads, therefore not reducing farming areas.

The Local Context

UPM’s participation in the SAN project is instrumental because it is the leading research university conducting ongoing studies in oil palm sustainability and provides the Malaysian context.

“Over the years, our team has conducted numerous studies related to landscape diversification in oil palm plantations,” says Entomologist and Biodiversity Scientist from UPM’s Department of Forestry Science and Biodiversity, Dr Norhisham Razi.

His team’s research ranges from introducing polyculture and livestock integration in oil palm to enhance biodiversity to investigating the effectiveness of natural predators like insects, birds and mammals in controlling pest insect species in oil palm plantations.

One exemplary case study was conducted on the MPOB Keratong (Pahang) plantation.

“By intercropping oil palm with secondary crops such as pineapple, bamboo and black pepper, the findings revealed significant increases in insect diversity and population within the plots compared to monoculture plots,” Norhisham explains.

“This case study underscores the potential of polyculture approaches to enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes.”

For the SAN project, Dr Norhisham’s team conducted surveys of insect biodiversity in smallholder palm farms and estates, compared local understory plants with introduced habitat islands, identified suitable local plant species and established plant beds within the oil palm understory to attract and maintain insect diversity.

Although MPOB (Malaysian Palm Oil Board) has introduced non-native beneficial flowering plants like Cassia cobanensis and Turnera sp under its IPM for bagworms guidelines, the SAN project focuses on using native plants already present in the Malaysian oil palm landscape.

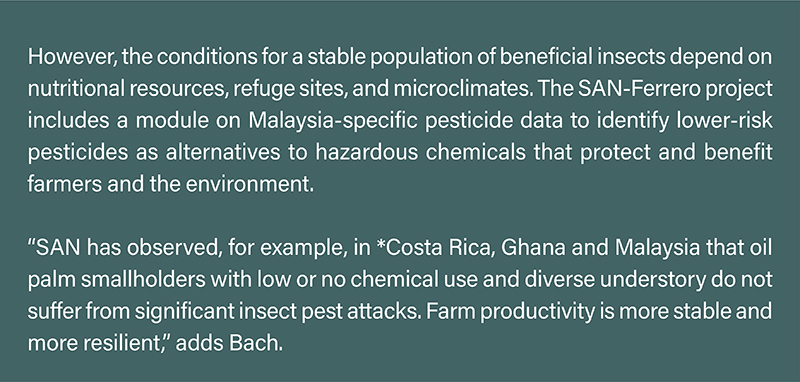

Outcomes and Status

The SAN-Ferrero project’s fieldwork began in early 2021 and was divided into several phases. In the early stages, the research team mapped out the farming practices of selected farmers in Perak and conducted a comprehensive survey of insects and plants to better understand the farm ecosystem. The survey findings identified 89 insect species and 121 host plant species (58% native plants), as well as the presence of crop-damaging pests like bagworms, rhinoceros beetles, and rats.

The research team discovered that certain plant species were associated with higher proportions of specific insect groups, Norhisham says.

For example, plants like straits rhododendron or sendudok (Melastoma malabathricum) and monkey’s potato (Coleus monostachyus) are associated with higher numbers of predatory insects like assassin bugs (Reduviidae), long-legged flies (Dolichopodidae) and scavengers, which indicate the plants’ potential to support natural pest control mechanisms. Parasitoid wasps like Cotesia metasae and Paraphylax sp. are potential biological control agents for bagworms.

“Essentially, integrating non-crop plant mixtures significantly enhanced insect diversity, stressing the importance of habitat complexity for natural enemies and increasing the resilience of the agricultural land’s ecosystem (agroecosystem) within monoculture plantations.”

Between 2021 and 2022, the UPM-Wild Asia team constructed habitat islands on four independent smallholders’ farm plots. During a bagworm outbreak in Perak in early 2023, Wild Asia found that rows of palms bordering or adjacent to the habitat islands on smallholder Neoh Ah Seng’s farm had far less bagworm infestation than neighbouring rows or farms. Neoh has been practising chemical-free farming on his Sg Kroh farm for over seven years. He is one of the earliest champions of WAGS BIO farming, dating back to 2018.

“Whilst we can’t equivocally say this (indicators from Neoh’s farm) is a result of the habitat islands and the wasps living in them, it is something that we need to try and design a way of testing,” Howes shares.

In phase three of the project, the team will finalise the tool package with the six best plant species (out of 20 trialled) for the habitat islands.

“We’ve built insect networks that showcase which beneficial insects are associated with these six plants and, in turn, which oil palm pests are controlled by these beneficial insects (predators and parasitoids),” says Bach.

Weaver ants on sendudok (Melastoma malabathricum) flower.

Howes adds that one of the upshots from this project for Wild Asia is realising the need to develop cost-effective ways and means to deliver these beneficial plant habitat islands for smallholder farms and larger estates. Phase three also includes planting 14 habitat islands, totalling 350 sqm, in a 35-ha block in an oil palm estate in Johor.

“So far, the collection and propagation of wild seeds seem to be a cost-effective approach, rather than buying seeds and seedlings from nurseries,” Howes explains. “We’re also looking at ways farmers can use existing habitat islands within their fields and the potential for “frond stack” rows to be a natural beneficial plant reservoir.”

UPM’s findings prove that maintaining understory plants within oil palm plantations is crucial for enhancing biodiversity and promoting natural pest control.

“By implementing IPM strategies and promoting landscape diversification, we can reduce reliance on agrochemical inputs and mitigate environmental impacts, aligning with sustainable development goals and ensuring the long-term viability of Malaysia’s oil palm industry,” Norhisham concludes.

* In a 2021 project in Costa Rica, SAN helped build the capacity and skills of smallholder farmers from an oil palm and cocoa cooperative to implement sustainable agricultural practices.

** An epiphyte is a plant, like ferns and orchids, that grows on another plant (e.g., on tree trunks). The results of SAN Phase 1 and 2 are now published in the journal Cogent Food & Agriculture (OAFA): A. R. Norhisham, M. S. Yahya, S. N. Atikah, J. Syari, O. Bach, Mona McCord, J. Howes, and B. Azha. (2024). Non-crop plant beds can improve arthropod diversity, including beneficial insects in chemical-free oil palm agroecosystems. Article ID: OAFA (2367383). https://doi.org/10.1080/.

References- *Mexzón, R.G. and Chinchilla, C.M. (1999) Plant species attractive to beneficial entomofauna in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) plantations in Costa Rica. ASD Oil Palm Papers (Costa Rica) No.19 (pp. 23-29).

- MPOB (2016) Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) Guidelines for Bagworm Control. Malaysian Palm Oil Board, Bangi. 41 pp.

- Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN)’s IPM Resources include presentations relevant to the SAN-Ferrero project.