Significant industry changes mean that strong ESG practices are now “must-haves” for corporations rather than a “nice-to-have”.

ESG or Environmental, Social & Governance has gripped the corporate world as a means of measuring and reporting on off-balance-sheet performance according to environmental protection, social responsibility and ethical and governance standards. Environmental criteria consider how a company performs as a steward of nature. Social criteria examine how the business manages relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities where it operates. Governance deals with a company’s leadership, executive pay, audits, internal controls, and shareholder rights.

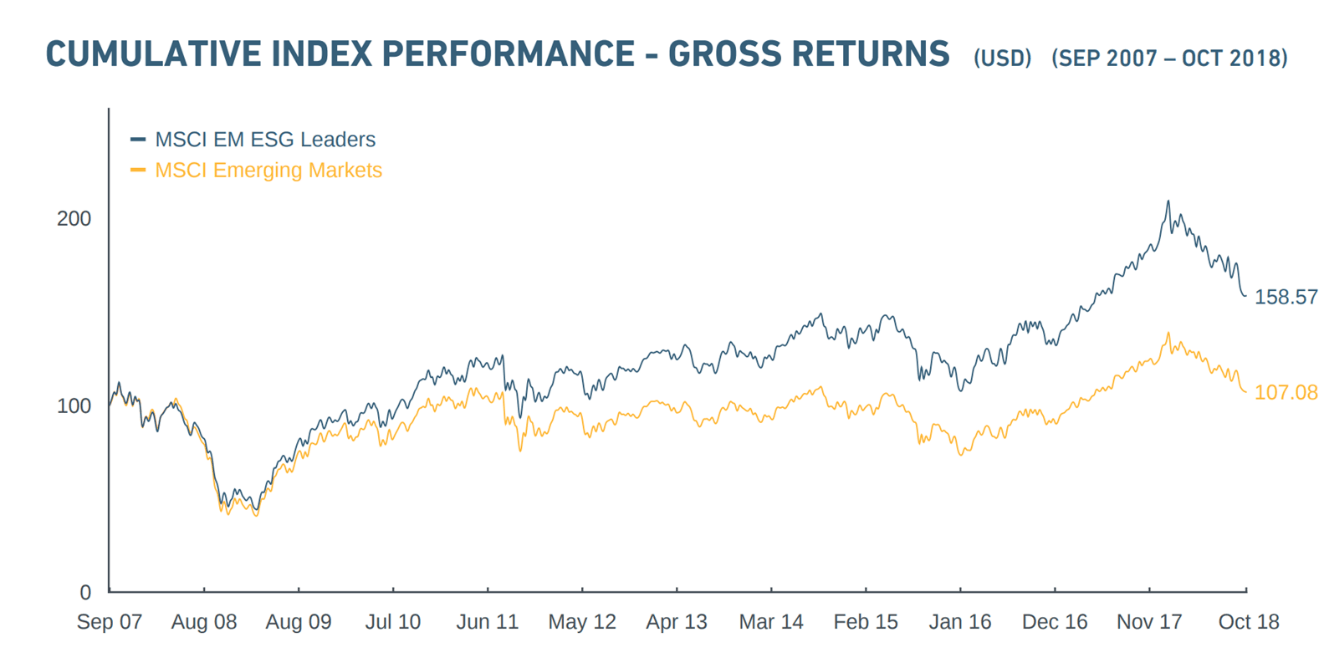

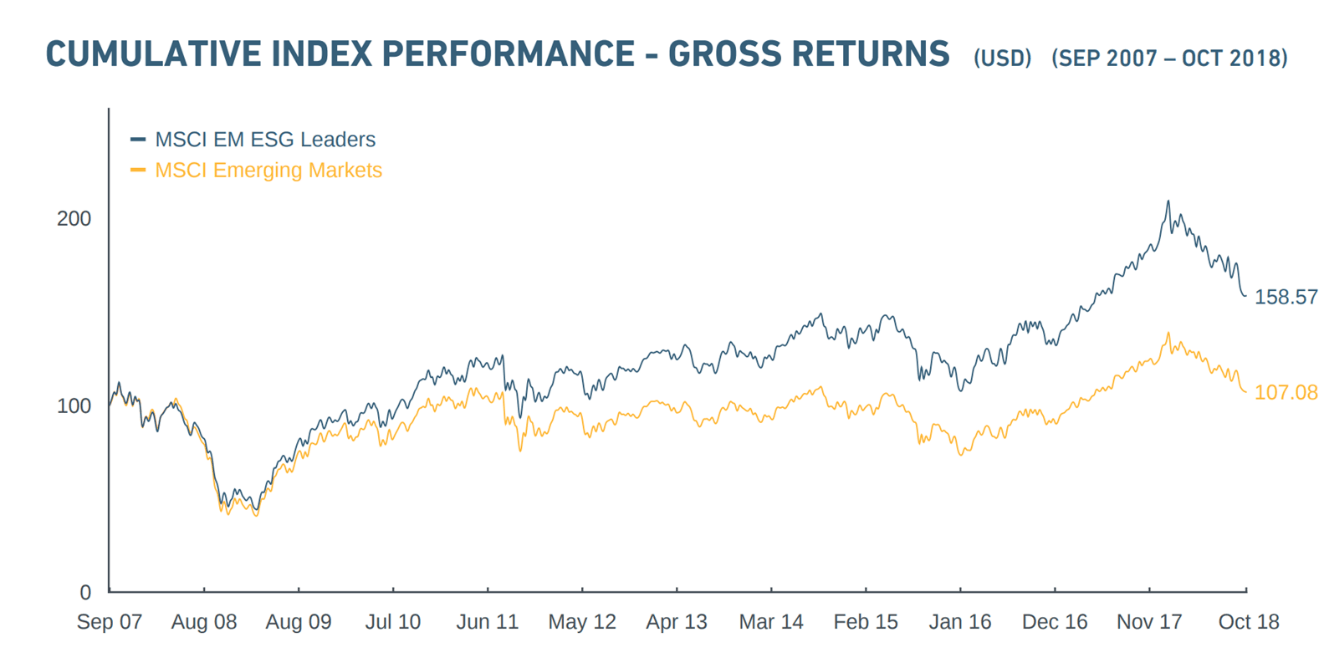

Furthermore, it is not just companies who are seizing the opportunity to demonstrate their ESG commitments to their staff, customers, suppliers and stakeholders; the investor world led by the likes of financial institutions, like BlackRock, are using ESG to examine the worthiness and ethical robustness of potential investees to ensure that the funds are spent wisely and responsibly. Unsurprisingly, market results show that companies with good ESG performance are good business performers.

Index Performance of ESG Companies (Source: Morgan Stanley Capital International)

Following the Paris talks on climate change in 2015, China’s commitment to reach peak carbon emissions in 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 followed suit by similar declarations from the US have set a pattern for the rest of the world to follow. ESG has, as a result, become a means interpreted by many energy-hungry companies and industries to report on how they will address the “net-zero carbon” challenge within the first half of this century. This is laudable and pushes much-needed capital into tackling climate change in areas of clean energy, alternative resources and new ways of business and lifestyles.

ESG doesn’t operate in a vacuum and it requires the internal stakeholders to effectively quantify ESG risk, value and impact and proactively mobilise efforts.

However, has the market swung too much on the “E” in ESG, at the expense of “S” and “G”?

Part of the reason why social issues get under-reported in businesses is that environmental issues are easier and more tangible to measure. Energy, water and waste are quantifiable making them easy topics for target-setting. Social issues on the other hand are not. Furthermore, businesses expect that such issues are more in the realm of governments to deal with rather than part of the corporate agenda.

“ESG should start at home with an organisation’s own staff. How companies treat their staff reflects much of the values and principles that the company stands for.”

Companies can, and should, do more on “S”

For example, ESG should start at home with an organisation’s own staff. How companies treat their staff reflects much of the values and principles that the company stands for. Health and safety at work, fair pay, labour rights, equal opportunity and freedom of association are some of the key social issues for workers. Measuring these need not be complicated as simple metrics like gender percentage in the Board, staff wellbeing and satisfaction levels, the number of reported incidents and number of training and development initiatives will indicate if a company is treating its staff well or not.

CSR or corporate social responsibility used to be the traditional outlet for community outreach whereby companies would donate to charities of their choice or encourage staff to volunteer their time to help the underprivileged. With ESG, however, communities are an integral part of the process through stakeholder engagement and determining “materiality”. Materiality is the principle of defining the social and environmental topics that matter most to the organisation’s business and its significant stakeholders, who are identified through a comprehensive stakeholder engagement process. This is important as given the wide range of topics on which a company can report in its ESG or sustainability report, the prioritisation of topics that are material and relevant to both the company and its stakeholders is necessary to prevent misreporting of “greenwashing”. For proper execution of ESG, communities are hence intrinsically involved.

The other area of social importance is in the supply chain. Responsible businesses take additional care in making sure that they source from reliable and ethical sources to avoid reputational damage. Issues such as modern slavery, child labour, health and safety and labour rights figure prominently in supply chains. A United Nations study reports that companies in the palm oil industry have faced numerous charges in the past on using coerced labour to farm the plantations. Equally hazardous practices have been encountered in the textile and fishing industries. Given the woeful record in such industries, supply chain scrutiny has become commonplace in ESG.

From a customer perspective, product safety and reliability are paramount. Companies must ensure that their products do not harm their consumers. The notorious case of the tainted milk powder in China in 2008 is an example of how far companies would go to make profits at the expense of their customers. Related to this is the dubious practise of marketing products that are harmful to people like tobacco and alcohol and exploiting the demand for these consumer goods. ESG puts these ethical issues into context by providing standards of behaviour and criteria by which to be judged. Performance measurements for businesses can be achieved through customer surveys, the number of complaints and levels of media coverage.

It should be noted that social performance must be measured not just by inputs but also by outcomes. Social impact measurements are a burgeoning field of study in social science measurable by improvements in education, knowledge, awareness, wellbeing and quality of life. As the adoption of ESG increases, no doubt such indicators will become common in future ESG reports.

“The threats of climate change and the depletion of natural resources have grown, so investors, in particular, tend to factor sustainability issues into their investment choices.”

ESG reporting derived from comparable, consistent and reliable data of an organisation’s ESG management performance and approach can reinforce accountability of its actions against concrete ESG targets.

Finally, governance is the ‘G’ in ESG that underpins the latter.

Governance looks into the roles and responsibilities of the management of a company through its board, shareholders and the various stakeholders in that company and provides a disciplinary framework that sets and abides by values, principles and ethical codes. Integral to governance is transparency and disclosure, which forms the backbone of public reporting, a key aspect of ESG. Regulators, NGOs, members of the public and investors use such disclosures to review companies in which they have an interest. The threats of climate change and the depletion of natural resources have grown, so investors, in particular, tend to factor sustainability issues into their investment choices. These issues include externalities i.e., influences on the functioning and revenues of the company that are not exclusively affected by market mechanisms.

That is not to say that social issues escape the attention of stakeholders. Activists are diligent in looking out for business activities that exploit human capital or impinge on human rights. Once revealed, such malpractices can have a damaging effect on reputation and subsequently on market worth.

A rising trend is sustainable finance. As mentioned earlier, investors are looking for responsible businesses to put their money in. Green bonds are becoming more and more popular in Asia to meet the costs for clean technology and climate-related infrastructure. The current global issuance of green bonds has reached a record high of US$290 billion representing an average annual growth of 36% over the past five years amounting to a cumulative total of more than US$1 trillion worth of bonds since 2007.

Green bonds are becoming more and more popular in Asia to meet the costs for clean technology and climate-related infrastructure.

There is also a growing market in social impact investment

In social impact investment, funds are put to projects aimed at uplifting societies and empowering communities. The metric commonly applied is social return on investment (SROI), which as the term implies looks at what you get for investments in projects or programmes that benefit society. Whilst impact investing has largely been the domain of family offices and foundations, personal wealth investors are also seeking responsible projects in which to sink their funds to do good and get decent returns. Examples of these are the following.

- Educate Girls, a Dasra portfolio organisation, has become the first Indian organisation to make use of Social Impact Bonds to launch a Pay by Results (PbR) programme; the programme receives support from Instiglio, a US-based non-profit social enterprise.

- Green Monday is a social movement and start-up group that aims to tackle climate change and global food insecurity by making low-carbon and sustainable living simple, viral and actionable. The four main issues Green Monday tackles are climate change, food insecurity, health issues and animal welfare, which are all heavily linked to the way we eat. Hence, the social enterprise’s main mission is to encourage as many people and organisations as possible to make Mondays “green”, that is, free of meat consumption.

- Kennemer Foods International, Inc. (KFI) is an agribusiness founded in 2010 in Davao, the Philippines specialising in the sustainable growing, sourcing and trading of high-quality agricultural crops. KFI is committed to rural development and aims to increase smallholder farmers’ yields and incomes by providing end-to-end support through its “growership” programme, promoting market transparency, providing fair value pricing for produce and implementation of sustainable farming practices. It engages an aggregation model, grouping farmers through networks, consolidators, cooperatives, associations as part of its service delivery.

So, in conclusion, ESG is more than just green measures and climate change but also about looking after people as well as the planet.

Whilst ESG issues are not mutually exclusive, it is important to pay attention to the social and governance dimensions of sustainability. It is telling that out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the UN in 2015, ten of them refer explicitly to social issues like poverty, hunger, education, inequality, right to work and social justice.

People clearly matter too.

About the Author

Dr Thomas Tang is a professional advisor to corporates on sustainability, climate resilience, urban design and social innovation. He is a UN Scholar, an adjunct professor and an author.